Putting ‘place’ at the heart of Indigenous education

Research 11 Aug 2016 4 minute read‘Place’ is more than geography. It has multiple dimensions, applications and interpretations, including cultural, economic, social, political and educational. Place must be at the heart of Indigenous education policy. Tony Dreise explains.

Putting ‘place’ at the heart of Indigenous education

Place-based strategy is a conceptual and strategic approach whereby local or regional communities are empowered to devise and implement solutions to multidimensional problems, or to seize opportunities at the local level. It is fundamentally different to programmatic or target group approaches to policy design and program delivery.

Place-based strategy, as a public policy approach, is particularly evident in communities of disadvantage.

Place-based approaches to Indigenous education

The idea of place as an approach to Indigenous education can be grouped into three categories:

- place as an approach to educational pedagogy and curriculum, for example, by playing a role in outdoor, cultural or environmental education

- place as a more holistic approach to improve educational outcomes for learners by improving their wider social environment, and

- place in education and training as an investment and intervention tool to break a cycle of locational, intergenerational and multiple disadvantage.

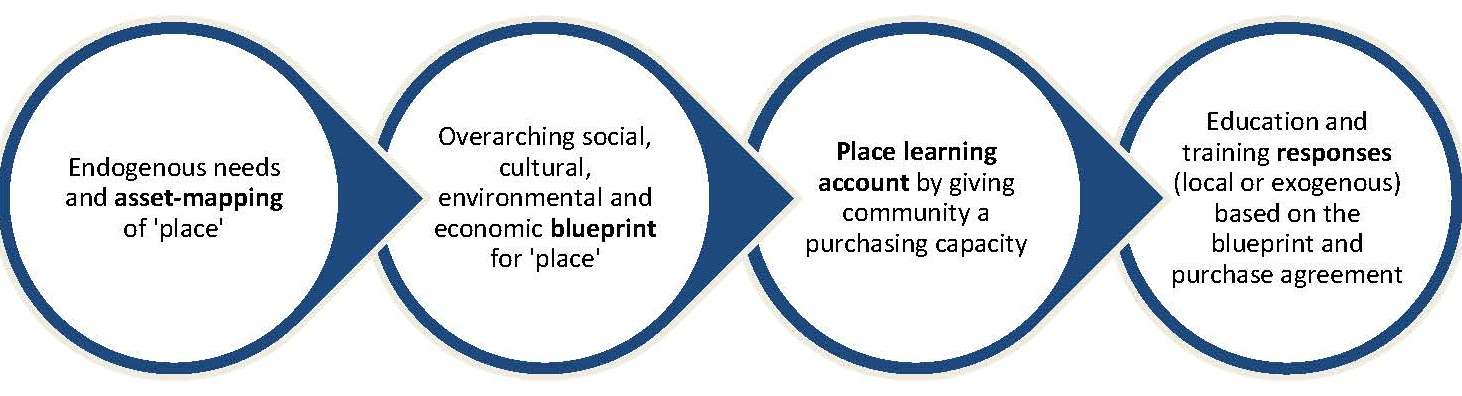

In practical terms, categories two and three could be advanced by providing communities of disadvantage with ‘place learning accounts’ driven by an integrated and holistic community development plan as opposed to limiting funding to institutionalised equity group programs. The following diagram helps illustrate a potential process in this regard.

Education as the engine room of place development

Research throughout the world finds that education and exchange are at the heart of human progress. And yet, governments too often see education as a silo that sits alongside other public policy portfolios, such as health and environment, as opposed to envisaging it as the engine room of place development.

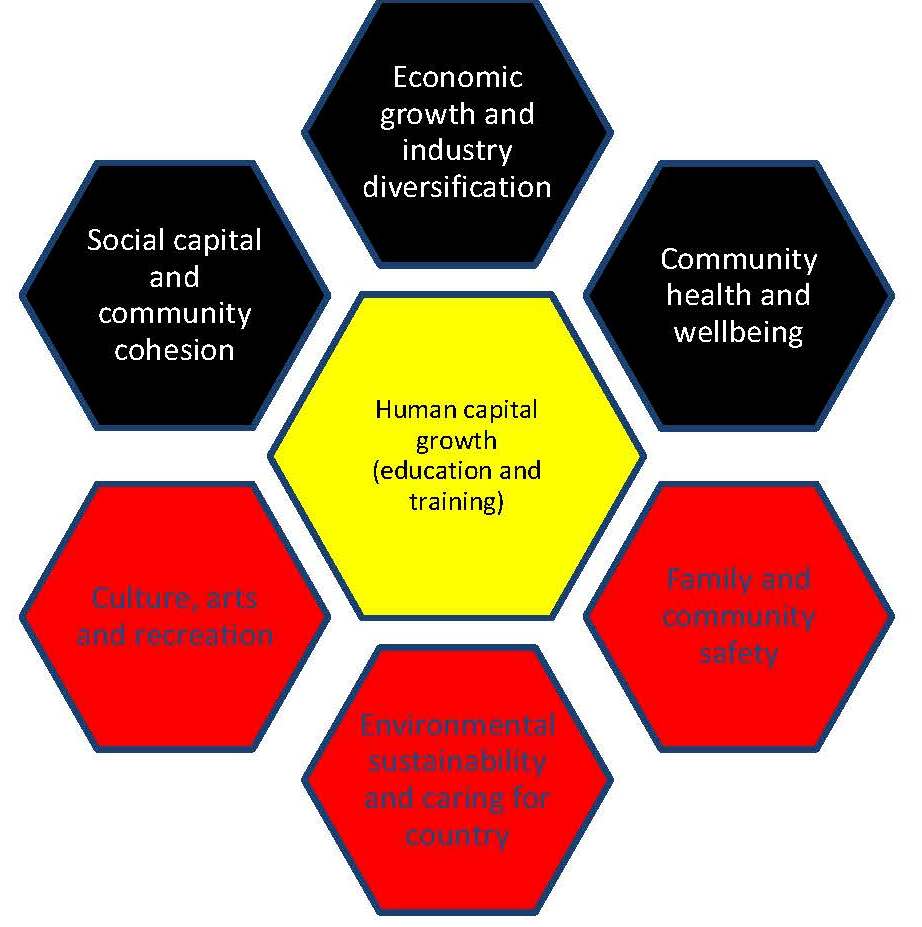

In communities that continue to experience entrenched and intergenerational disadvantage – with little signs of turning the corner – ‘positive disruption’ is ideal with education at its centrepiece, as the diagram below shows.

Learning, Earning, Yearning

With regard to Indigenous communities, socioeconomic considerations are but one consideration in place design. As the ‘Learning, Earning, Yearning’ model I have devised below illustrates, ‘place’ has a relationship with culture and identity, pathways and opportunities, and local employment.

As the model shows, positive place development is more likely to become a reality when it is underpinned and spurred by a community’s capacity to pursue entrepreneurialism, agency and creativity. This means communities need to be resourced to foster such capabilities.

Moving forwards

There is much we know about place-based theory and implementation, but equally there is much we do not know. What we do know is that there needs to be stronger interest among governments in place thinking, trialling, innovation and evaluation.

For any model to work, governments and other funders (such as philanthropists or corporations) would be wise to position human capital growth and place development at the heart of Indigenous policy and program design.

Further information:

This is a summary of the article ‘First people, first place’, published by the Victorian Adult Literacy and Basic Education Council (VALBEC) in Fine Print in 2016.

Learn more about Tony Dreise’s Learning, Earning, Yearning model.